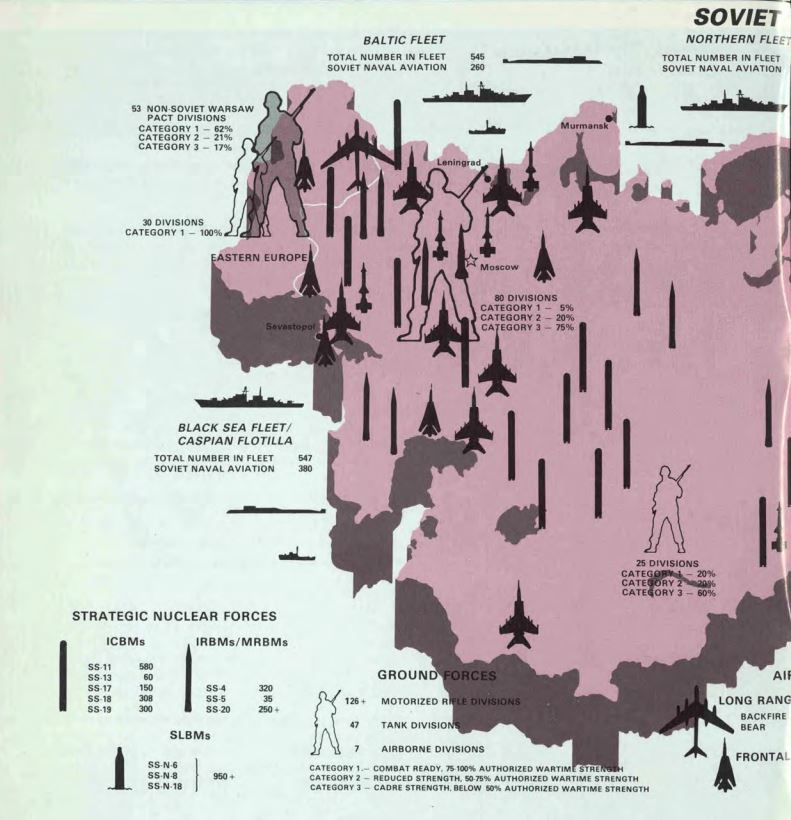

DIA’s recently released report on Soviet Russia Military Power is an interesting offering. In the 1980s, it’s forerunner titled Soviet Military Power served two purposes: first highlight the Soviet threat (typically exaggerating it to make a strong argument for defense spending) and second inform the public discussion on Soviet capabilities. This report does some of the former, and a bit of the latter. Disappointingly it is of lower production quality, lacking many of the maps, graphics, and photos that Soviet Military Power came with (my favorites among the old graphics were big manly Soviet ICBMs drawn next to very small American ICBMs). Thus, the report already achieves a part of it’s mission: demonstrating why we need more funding for higher quality reports on Russian Military Power.

Soviet Military Power 1983 (this is how you do it right)

Soviet Military Power had no footnotes, and did not identify which agency had produced it, while this report has hundreds of footnotes to Russian authors, journalists, and even wikipedia. In this respect it is not distinguishable from other think tank products on the Russian military, and some respects compares poorly to Sweden’s FOI reports titled “Russian Military Capability” in terms of information offered. Below I discuss the better parts of the report, what it gets wrong, and key issues to consider when thinking about Russian military power.

On the whole the report seems a misspent opportunity. It offers some interesting bits of knowledge on the contemporary history of Russian armed forces, reforms, and current thinking on doctrine. However, one cannot read this product and walk away with an appreciable knowledge on the size, disposition, or capabilities of Russian armed forces. Those worried about a high end fight in the Baltics, or anywhere else for that matter, are best off reading FOI’s work or that of informed blogs in order to understand Russia’s order of battle, force posture, and the like.

The report presents vignettes, deep dives into subjects like Russia’s gas turbine production, yet nothing in terms of a functional order of battle. You may learn that a VDV division now has a company of T-72 tanks, but not how many troops are in the VDV and where they’re based. What can Russia really do? What does it plan to do? Does it have the forces to realize these ambitions, etc. remain open ended questions. This report has a a lot of sporadic information on what is happening, but is quite poor in explanations for why any of these changes, procurement, or deployments have taken place.

The Good:

- The report does a great job summarizing Russian threat perceptions, much of which is established knowledge, but nonetheless there is a solid review of recent doctrines, statements, etc. Here we can read about the besieged fortress mentality, general perception that the U.S. is trying to conduct regime change in Russia’s near abroad, and looking for the opportunity to do so in Moscow, along an acknowledged state of confrontation. Russia sees the U.S. as seeking to contain it and punish it for pursuing an independent foreign policy.

- There is a decent review of the transition which Russian armed forces underwent after the collapse of the USSR, reforms of 2008-2012, and some of the concepts discussed from the 1990s into the early 2000s and today. Unfortunately, much of the information seems dated, and the report’s coverage stops being actual as we get to 2014-2015 in terms of delving into important changes ongoing in the Russian military and identifying the factors driving them.

- Capabilities and doctrines are covered in an informed manner. It is difficult to find this gamut of information brought together elsewhere in terms of other publications, and without a panicky tone, which has become customary in any discussion on Russian doctrine.

The not-so-good:

- One can find little on the actual size of Russian armed forces, and ground force numbers cite IISS annual Military Balance publication, which is notoriously wrong in terms of order of battle. Hence this is a report on Russia Military Power that offers a dearth of information on the basic size and disposition of Russian armed forces today. The nature of Russia’s military power, where it is concentrated, and against whom, remains an open question at the end of this report. There are no ranges for capabilities, forces marked on the board, or much else that demonstrates what has changed in recent years.

Where are the ranges of things? (from 1981)

- There is no discussion of Russia’s tier one special forces (KSO) and the addition of this SOF toolkit in 2012 to Russia’s military, while the overall numbers on current Spetsnaz appear greatly inflated at 20,000-30,000, when there are better figures out there in publications. Other trends in the expanding force structure, such as addition of logistics units, are glossed over.

- Important information that would prove quite useful to anyone trying to understand the current state of Russian armed forces is missing across the board. One cannot discern from the writing what Russia’s main battle tank actually is (hint it’s the T-72B3), how many tanks they have today, or the current numbers in terms of Su-30SM, Su-35S, or Su-34 acquisition for the air force. The true disposition of Russian air defense, meaning how many units have S-400,or upgraded S-300PMU2, or S-300V4 variants, is also missing. Indeed the entire air defense section is quite glib for a military that depends so much on integrated air defense in order to operate, and potentially counter what it sees as the U.S. preferred way of war.

Here is what this info might look like based on the 1981 edition:

- How sustainable is Russia’s force? What is the share of conscripts to contractors? The relevance and impact of demographic trends over the medium and long term on the available pool of manpower is notably absent. Russia has been successful in increasing the share of contract servicemen in its armed forces relative to conscripts, at an overall force size somewhere between 900,000-930,000 today depending on figures – these are the more important indicators to observe in terms of Russian military power. However there is also plenty of statistical cheating, so it would be useful for DIA to offer some sort of data point not footnoted to wikipedia or IISS on the state of Russian armed forces.

- Defense budget is given short shrift, and some of the information is poorly interpreted. From the allegedly ‘real 30% cut in defense spending’ 2016-2017 which was covered extensively on this blog and by others (this 30% cut is not a thing), the budget went from 3.16 trillion to 2.84 trillion, and the endless propensity to count Russian spending in 2017 USD. For example Russia’s original state armament program 2011-2020 was listed at ~660 billion USD (in 2011 figures), but looking backwards with the much devalued currency exchange rate of today, it is converted into less than half that. This is a terrifyingly common mistake, going back in time to recalculate Russia’s defense spending in dollars. Of course the USD figure is irrelevant either way, since Russia does not buy its equipment from the U.S., and given spending adjusted for PPP the purchasing power of that budget is much higher than what Western countries get out of their budgets.

- The conversation on deterrence generalized thinking in Russia and equally in the West. There is no history offered on the evolution of Russian views of deterrence, coercion, or escalation. The information presented lacks context, particularly in recent years. What is the reason for adoption of one particular strategy or another, and the driving factors in Russian thinking on this subject moving forward? What’s missing: a conversation on current Russian thinking on deterrence in conflict, escalation control, and which U.S. capabilities influence their decision making, etc. Why does Russia have the strategy it does, and how is it evolving?

- The section on indirect action and strategic deterrence is a confounding mix of jargon, terms, and buzzwords, i.e. it reads like it was written by a government agency. “Indirect action is a component of Russia’s strategic deterrence policy developed by Moscow in recent years. Its primary aim is to achieve Russia’s national objectives through a combination of military and non-military means while avoiding escalation into a full blown, direct, state-to-state conflict. Drawing on a combination of facets from Russia’s whole-of-government or interdepartmental strategy and overt or covert military means, indirect action seeks to exploit weaknesses and fissures in target countries in order to fulfill Moscow’s desired national goals.” We need to get ‘whole of government’ out of the government lexicon in terms of describing either our own or someone else’s approaches.

Things that are kind of wrong (a few samples):

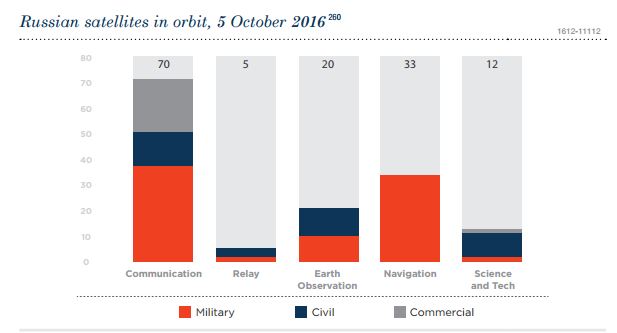

- Report describes Russia’s space program as formidable when in reality it is one of the biggest disasters in Russia’s industry, in terms of production quality, number of launches, ability to sustain satellite networks, etc. The early warning satellite network went down years back and they’ve only just managed to get a second launch detection satellite up in recent month out of a desired ten – this is just one example. Note all Proton-M rockets grounded over defective engines back in January. The coming state armament program GPV 2018-2025 intends to address some of these well publicized problems in Russia’s space program.

Numbers without context are difficult to analyze. Is this number of satellites how many they need to sustain a functional network? How are recent launches doing? What is the average number of years a Russian satellite can stay up? Oh, and how is the new satellite early warning network going? (figures from the report below)

- Report suggests Russian acquisition is investing in out-of-area operations. There is nothing to substantiate that besides long range strike capability. Russia is not investing in the sea lift, logistics sustainment, a blue water navy, or other capacities for combat operations distant from its borders. Equally there is nothing to indicate a preparation for the occupation of other countries, an operational reserve, or other capacity to operate “out of area” – of course we should note that Russia’s area is quite vast but in general the armed forces are clearly setup for fights ‘across the street’ more so than anything else.

- There is no coverage of ground force restructuring from brigades to divisions, including three new divisions based around Ukraine, one across the border from Kazakhstan, a new Combined Arms Army in the Southern Military District, etc. Information on brigades, and battalion tactical groups seems woefully dated in terms of the lessons Russian ground forces learned in Ukraine and how they intend to fight a high-end contingency. Is Russia really going to use battalion tactical groups in a fight with a peer adversary, or are the new divisions an indicator of larger formations to come? Also the new divisions seem to have different TOE depending on which ones you’re looking at, some are bigger than others.

- Report’s numbers are internally inconsistent in terms of order of battle, for example long range aviation is listed as 16 Tu-160, 60 Tu-95, and 50 Tu-22 bombers (this adds up to 126) and on the same page the report lists Russia as having 141 bombers. It’s hard to cite a report that can’t keep its numbers straight. There is no mention of Su-34 or Su-24 bombers and the air force ORBAT section is literally incomprehensible. Another example: report says there are 40 active reserve and maneuver brigades + 8 divisions for a total of 350k ground troops. At 4,500 per brigade as suggested in the report (which is wrong but ok), that’s about 180,000 troops in brigades which leaves 170,000 in 8 maneuver divisions – a number that is completely impossible. It’s unclear how 40 brigades and 8 divisions add up to 350,000 ground troops – is that counting VDV units or not? Lots of basic math problems in this report (too many for comfort).

Here is a sample page from the new DIA report (note the bomber numbers in text versus table)

This is what ORBATs could look like, from 1981:

Things to consider when ruminating on Russian Military Power:

- The shifting focus first away from Russian ground forces in 2008-2014, and then back to larger ground force formations and the VDV after the conflict with Ukraine, which will likely be reflected in the GPV 2018-2025, i.e. more cash for ground forces compared to the previous armament program. A trend first away from land power to investing in other services, and then back to land power and larger unit formations after 2014.

Remember all the new divisions and ground force formations being created post-2014, and units shifted back to where they were prior to the 2008-2012 reforms:

- An understanding of where Russia stands in terms of its ability to conduct non-contact warfare, mass long range fires with precision guided weapons, and some sense of the stockpile. How far is it on the path to achieving non-nuclear deterrence, i.e. conventional deterrence with its forces, both in terms of defense and ability to strike peer adversaries. The role of cyber, EW, information operations in a unified concept of coercion or deterrence, etc.

- Evolution of Russian air defense and aerospace forces, rhetoric versus reality in terms of capabilities and rate of modernization. How Russia’s General Staff views its ability to defend against Western air power and their confidence level given pace of modernization on air defense being a viable deterrent.

- Russia’s nuclear arsenal modernization, role of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and emphasis on different elements of the triad, or more honestly ‘quad’ which is a better way to assess Russian nuclear forces.

With DIA’s Russian Military Power out one can only hope that Russia will release its own response, which during the Cold War was called “Whence the threat to peace,” so that we can return to that old familiar publication tit for tat. Bottom line, this is not a bad start, but on the whole DIA’s publication greatly lags it’s predecessor, and raises more questions than answers when it comes to Russian military power.

Reblogged this on vara bungas and commented:

Great piece of analysis

LikeLike