This text is from a chapter published in the edited volume: THE FUTURE OF THE UNDERSEA DETERRENT: A GLOBAL SURVEY by Australian National University, titled The Role of Nuclear Forces in Russian Maritime Strategy. I highly recommend you read the book, as there are many wonderful sections on other countries. Also the footnotes and references can be found there, as I’ve yet to figure out how to port them into this type of medium.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Although Russia is one of the world’s preeminent continental powers, Russian leaders have historically rendered considerable attention to sea power. Through sea power, Moscow could establish Russia as a great power in international politics outside of its own region. Sea power served to defend Russia’s expansive borders from expeditionary naval powers like Britain or the United States, and to support the Russian Army’s campaigns. With the coming of the atomic age, the Soviet Navy took on new significance, arming itself for nuclear warfighting and strategic deterrence missions. The Soviet Union deployed a capable nuclear-armed submarine and surface combatant force to counter American naval dominance during the Cold War. The modern Russian Navy retains legacy missions from the Cold War, but has taken on new roles in line with the General Staff’s evolved thinking on nuclear escalation, while adapting to the inexorable march of technological change that shapes military affairs.

The Russian Navy has four principal missions: (i) defense of Russian maritime approaches and littorals (via layered defense and damage limitation); (ii) executing long-range precision strikes with conventional or non-strategic nuclear weapons; (iii) nuclear deterrence by maintaining a survivable second-strike capability at sea aboard Russian nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs); and (iv) naval diplomacy, or what may be considered to be status projection. Naval diplomacy in particular rests with the surface combatant force, chiefly the retinue of inherited Soviet capital ships (cruisers and destroyers), which while ageing remain impressive in appearance. Meanwhile, the Russian Navy, like the Soviet Navy before it, is much more capable beneath the waves, arguably the only near-peer to the United States in the undersea domain.

Regionally, Russian policy documents convey a maritime division in terms of the near-sea zone, the far-sea zone, and the ‘world ocean,’ while functionally the Russian General Staff thinks in terms of theatres of military operations. The Navy is naturally tasked with warfighting and deterrence in the naval theatre of military operations, defending maritime approaches, and supporting the continental theatre. Russia’s navy remains a force focused on countering the military capabilities of the United States, and deterring other naval powers with conventional and nuclear weapons. Over time, it has also acquired an important role in Russian thinking on escalation management, and the utility of non-strategic nuclear weapons in modern conflict.

Continuity in Naval Strategy: The “Bastion” concept endures

Russian naval strategy has proven to be evolutionary, taking its intellectual heritage from the last decade of the Cold War. Nuclear and non-nuclear deterrence missions are deeply rooted in concepts and capabilities inherited from the Soviet Union; namely, the bastion deployment concept for ballistic submarine deployment, together with the more salient currents in Soviet military thought derived from the late 1970s and early 1980s, being the period of intellectual leadership under Marshal Ogarkov, Chief of Soviet General Staff at that time.

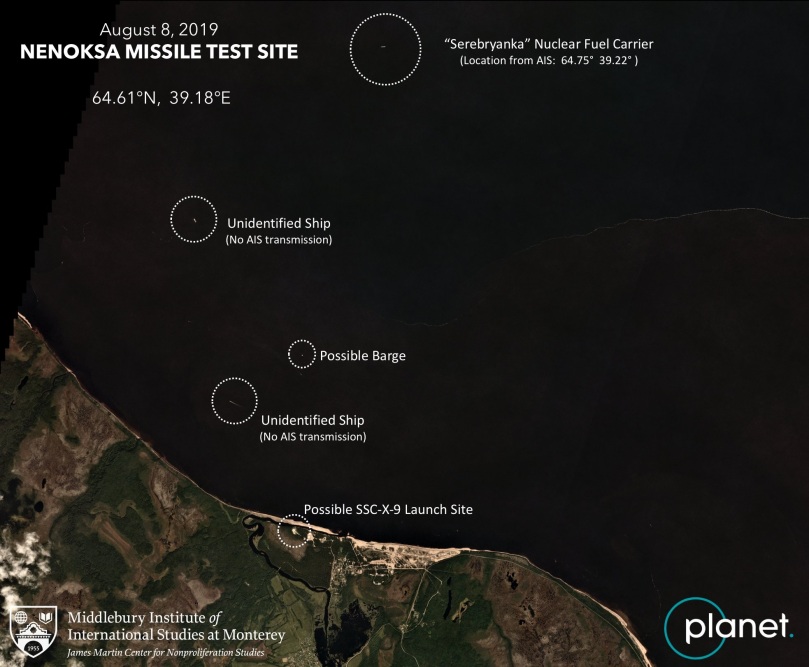

Strategic deterrence and nuclear warfighting in theatre proved anchoring missions for the Soviet Navy during the Cold War. In the 1970s-80s it had become widely accepted that the Soviet Union adopted a “withholding strategy,” as opposed to an offensive strategy to challenge US sea lines of communication. The Soviet Northern and Pacific Fleets would deploy ballistic missile submarines into launch points in the Barents Sea and the Sea of Okhotsk, protected by attack submarines, and a surface force geared around anti-submarine warfare (ASW). US analysts termed these protected ballistic missile submarine operating areas “bastions,” and the name stuck.

The merits of the strategy were always questionable, since the Soviet Union was geographically short on unconstrained access to the sea, unlike the United States, while having a plethora of land available for land-based missiles. However, the Soviet Navy deployed a sizable ballistic missile submarine force (more than 60 strong) as part of a nuclear triad. Defending these bastions to maintain an effective survivable deterrent drove shipbuilding requirements for a surface combatant force, and a large submarine force to fend off penetrating US attack submarines. Consequently, ballistic missile submarines proved the linchpin in Soviet naval procurement, and capital ships were designed to defend the SSBN bastions rather than simply enhance anti-carrier warfare or forward strike missions.

Although from a competitive strategy standpoint it might have made sense for Russia to walk away from SSBNs, leveraging road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) as a cheaper survivable nuclear deterrent, this was not the direction elected by the Russian General Staff. Russia’s military clings to a sea-based nuclear deterrent that is incredibly expensive, arguably indefensible from adversary counterforce attacks, and makes little strategic sense in light of the country’s current nuclear force structure. Russia’s current ballistic missile submarine force includes three Delta III-class (only one of which is operational), six Delta IV-class and three of the newer Borei-class SSBNs, for a total of ten operational SSBNs. The likely deployed warhead count at sea is somewhere in the range of 600–800. The bulk of the force, nine submarines, are stationed in the Northern Fleet, while three submarines are currently assigned to the Pacific. The Borei-class SSBN program, together with the newer Bulava SLBM, is the single most expensive item in Russia’s State Armament Program. Russia is set to procure eight to ten Borei-class submarines by the early 2020s, first phasing out the ageing Delta III-class, and subsequently the Delta IV-class.

The problem with this strategy is that in the 1990s the Soviet Navy melted away, reducing in strength from approximately 270 nuclear-powered submarines in the late 1980s to about 50 or so today, at an operational readiness that likely cuts those numbers further in half. Similarly, the large surface combatant force has declined precipitously, transitioning to a green-water navy, with limited ASW capability. Russia’s submarine force is less than twenty per cent the size of the late Soviet Union’s, and the surface combatant force is much smaller, to say nothing of maritime patrol aviation. Russia’s focus on the Arctic is driven in part by a desire to better secure this vast domain from aerospace attack, and provide the infrastructure to better defend SSBN bastions, especially as passage becomes passable for surface combatants.

It is worth noting that Russian submarine operations have re-covered after declining precipitously in the early 2000s. Since then, the Russian Navy has been buoyed by a sustained level of spending on training and operational readiness, military reforms leading to almost complete contract staffing in the Navy, along with procurement of new platforms. Senior Russian commanders frequently issue pronouncements about increased time at sea, training, and patrols, though a high operational tempo eventually inflicts a cost to readiness.

Russia continues to modernize its existing ballistic missile submarines, and field new ones, as part of a legacy strategy inherited from the Soviet Union. Continuity in the “bastion” strategy may provide the Navy with an argument for spending on Russia’s general-purpose naval forces, more so than it provides a survivable nuclear deterrent. Comparatively, Russia now fields a large force of road-mobile ICBMs, including RS-24 YARS (SS-27 Mod 2), and Topol-M (SS-27 Mod 1), with two regiments still upgrading to this missile. Despite the fact that a growing share of Russian nuclear forces is becoming road-mobile, reducing the need for sea-launched ballistic missiles, the Navy retains a prominent strategic deterrence mission, enshrined in key documents outlining national security policy in the maritime domain.

New Roles: Non-Nuclear Deterrence and Escalation Management

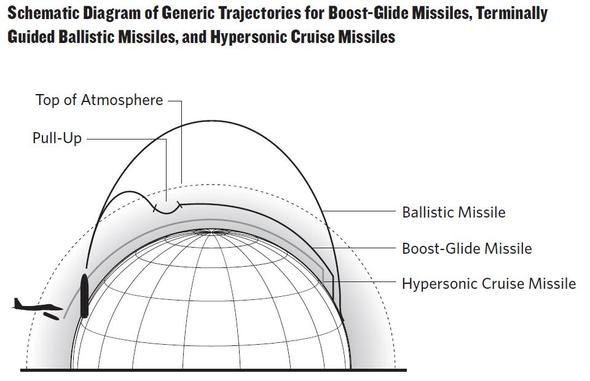

Relatively unchanged operational concepts for deploying SSBNs disguise tectonic shifts in Russian thinking about nuclear escalation, and the role of naval forces in strategies aimed at escalation management and war termination. There are profound changes occurring at present in Russian military strategy stemming from the debates in Russian military thought as far back as the Nikolai Ogarkov period of 1977–1984. In the 1980s, the Soviet General Staff began focusing on the rising importance of long-range precision-guided weapons, particularly cruise missiles, and their ability to attack critical objects throughout the depth of the adversary’s territory. Ogarkov, the Chief of the Soviet General Staff at the time, advocated for the belief that precision conventional weapons could be assigned missions similar to that of tactical nuclear weapons from the 1960s-1970s. These were the fountainhead of present-day Russian discourse on non-contact warfare, the dominance of precision-guided weapons on the battlefield, and their ability to decide the conflict during an initial period of war.

Observing modern conflicts in the 1990s and 2000s, the Russian General Staff came to adopt the need to establish “non-nuclear deterrence,” premised on the strategic effect of conventional weapons, and the consequent shift of non-strategic nuclear weapons into the role of escalation management. Nuclear weapons originally meant for warfighting at sea, and in Europe, were hence valued for their ability to shape adversary decision-making, by fear inducement, calibrated escalation, and management of an escalating conventional conflict. Non-strategic nuclear weapons were subsequently incorporated into strategic operations designed to inflict tailored or prescribed damage to an adversary at different thresholds of conflict.

The Soviet Navy was never designed to fulfill this vision, but the modern Russian Navy seeks to centre its role along these doctrinal lines as part of joint operational concepts called strategic operations. Soviet naval forces retained a strong nuclear warfighting mission, seeing tactical nuclear weapons as a critical offset to US naval superiority, and contributing land attack nuclear-tipped cruise missiles to general plans for theatre nuclear warfare in Europe. However, by acquiring the ability to conduct precision strikes on land with cruise missiles, along with other types of multi-role weapons, the Russian Navy could now contribute to both the conventional deterrence and the non-strategic nuclear employment mission.

Official statements by Russian military leaders, and doctrinal documents, emphasize the importance of precision-guided weapons in the Russian Navy, and the belief that under “escalating conflict conditions, demonstrating the readiness and resolve to employ non-strategic nuclear weapons will have a decisive deterrent effect.” According to different estimates, Russia retains roughly 2,000 non-strategic nuclear weapons, a significant percentage of which appear assigned for employment in the maritime domain, either by the Russian Navy or land-based forces supporting the naval theatre of military operations. The means of delivery are decidedly dual capable, with the same types of missiles being able to deliver conventional or nuclear payloads with fairly high accuracy.

Russian strategic operations envision conventional strikes, single or grouped, against critical economic, military, or political objects. These may be followed by nuclear demonstration, limited nuclear strikes, and theatre nuclear warfare. To be clear, theatre nuclear warfare is not new to Russian nuclear doctrine, but was always the expected outcome of a large-scale conflict with NATO during the Cold War. For much of the 1960s through to the 1980s, the Soviet Union anticipated at best a two to ten-day time window for the conventional phase of the conflict. However, unlike the nuclear weapons of the Cold War, precise means of delivery, together with low-yield warheads, have rendered nuclear weapons more usable for warfighting purposes with a substantially reduced chance for collateral damage. Scalable employment of conventional and nuclear weapons leverage the coercive power of escalation, whereby strategic conventional strikes make the actor more credible in employing nuclear weapons in order to manage escalation. In the context of an unfolding conflict, these weapons are not necessarily meant for victory, but to break adversary resolve and terminate the conflict.

The Russian Navy, although limited in the number of missiles it can bring to bear due to constrained magazine depth, retains a prominent role in the execution of these missions, particularly in the early phases of conflict. In this respect, submarines like the Yasen-class, and others able to deliver nuclear-tipped cruise missiles to distant shores, should be considered as important elements of sea-based nuclear deterrence at a different phase of conflict, and perhaps no less consequential than SSBNs.

Again please check out the edited volume for other great works on undersea nuclear deterrence, by other authors, and for references.