I’ve recently put out an article on Russia’s Avangard hypersonic boost-glide system in the well known Russian journal The New Times, under the title “ЧТО ВСЕ-ТАКИ ПУТИН ПОДАРИЛ РОССИЯНАМ НА НОВЫЙ ГОД,” but for those interested, please find the unedited English version below, which hopefully covers the subject in some depth.

Earlier in March 2018, Vladimir Putin announced at his annual address to the federal assembly that a Russian hypersonic boost-glide system, named Avangard, would start entering serial production. Subsequently on December 26th, 2018 Russian officials claimed that they had successfully conducted a test from the Dombarovsky missile site, to the Kura test range on Kamchatka, some 3,760 miles away. Russia’s president proudly announced that the system as a wonderful ‘New Year’s gift’ to Russia. According to Putin’s statement, the hypersonic glide vehicle is able to conduct intensive maneuvers at speeds in excess of Mach 20, which would render it “invulnerable” to any existing or prospective missile defenses. In this article I will briefly explore the logic behind Russia’s hypersonic boost glide program, recent claims of technological accomplishment, and the strategic implications of deploying such weapon systems.

Despite rather questionable public statements about the technical characteristics of this weapon system, a number of which appear inconsistent, it is clear that Russian military science has made considerable advancements along one of the most sophisticated axis of weapons research. While claims pertaining to the readiness of this system to enter serial production, and operational service, are probably exaggerated, the more important questions are conceptual. More than likely Russia will be able to deploy a hypersonic boost glide system in the 2020s, perhaps alongside other hypersonic weapons projects, but the promise of this technology was always at the tactical-operational level of war, not strategic. This was never considered a ‘game changer’ as a system for the delivery of strategic nuclear weapons. If anything, Russia has invested a substantial amount of money, and years of research, in overdoing its strengths. Beyond a somewhat militant demonstration of ‘Russian national achievement’ for domestic audiences, it’s unclear if this weapon system truly answers Russia’s strategic challenges in the coming decades. The question is not whether it works, or when it will work, but does it even matter?

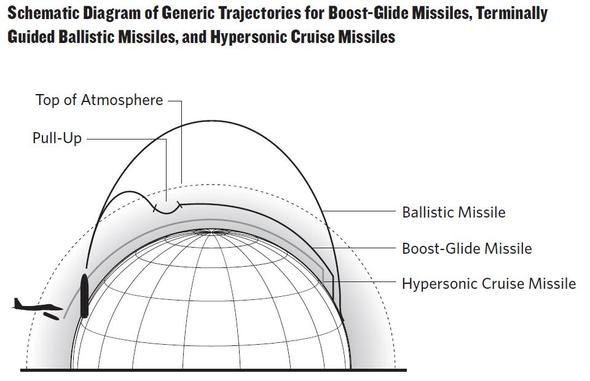

Hypersonic boost glide weapons function by using a multi-stage ballistic missile as the boost phase, throwing a vehicle into near earth orbit, which then descends and begins gliding at hypersonic speeds along the edge of the atmosphere. As the vehicle descends back to earth, it pulls upwards, and begins skimming the atmosphere in a ‘glide’ phase, before diving downwards onto its target at the terminal phase. Russia has spent years developing this technology under a project referenced as Object 4202, which married a series of experimental hypersonic glide vehicles, such as the Yu-71, with a liquid fueled ICBM УР-100УНТТХ (NATO designation SS-19 mod 2 Stiletto). This system builds on the Soviet Union’s extensive research into hypersonic weapons programs , including work on a hypersonic-boost aircraft named «Спираль», a modified S-200V surface-to-air missile under the project name Холод, and hypersonic cruise missile programs, such as Kh-80 and Kh-90 GELA (гиперзвуковой экспериментальный летательный аппарат).

Although claimed successes in testing may have come as a surprise in 2018, in truth Russian officials have been announcing tests of a hypersonic boost glide vehicle, using the УР-100УНТТХ missile, as far back as the strategic nuclear forces exercise in 2004. Hence, this particular system has been in publicly acknowledged development for at least 14 years, and the glide vehicle itself for quite a few years beforehand. The booster, УР-100 (SS-19), is a 105 ton liquid fueled silo-based missile, which together with the boost glide vehicle payload proved too long for a standard silo. Hence this system is being tested in a modified R-36M2 silo (SS-18 Satan), and although it is being developed with the УР-100, it is meant for the much heavier liquid fueled missile currently in testing, RS-28 Sarmat. While the question of boost method may seem a technicality, the boosting mechanism is actually quite deterministic of the strategic role this weapon can play, as I will discuss a bit later in this article.

However, the principal challenges with this system have little to do with the decades established technology of intercontinental ballistic missiles, or boosting objects into near earth orbit. Hypersonic boost glide vehicles, if successful, represent a major breakthrough in material sciences, as the object must be able to withstand incredibly high temperatures with the payload and guidance system intact. Although impossible to verify, Russian announcements can often be categorized as ‘true lies,’ impressive sounding figures that have some factual basis, but are inevitably inaccurate. The proposition that the vehicle can reach mach 27 is likely true only during the brief return phase, when it is falling back to earth like a rock from near earth orbit, prior to beginning its hypersonic glide at the edges of the atmosphere. The vehicle itself will have considerably different speeds during the pull-up, glide, and dive to target phase, while having to endure incredible temperatures.

Below are a few graphical illustrations available on the web

In U.S. testing of an analogous system in 2011, Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 (HTV-2), the vehicle was able to sustain glide at mach 20 speeds for three minutes, enduring a temperature of 3500 Fahrenheit. These figures track with Russian statements on temperatures experienced, but the actual speeds and altitudes at which the Russian vehicle is able to glide, and whether the systems actually survive this experience, remain a mystery. Although Russia’s defense sector seems to have made progress on this weapon system, claims that it is ready for serial production, or operational deployment in the near future, should be treated with educated skepticism. Ironically, the most significant potential breakthrough is in material sciences, not in building a seemingly scary strategic weapon.

Yet the rationale for Avangard seems less than straightforward when compared to other Russian hypersonic weapons programs, including the Tsirkon 3M22 scramjet hypersonic cruise missile, and the Kinzhal Kh-47M2 aeroballistic missile. Those are operational depth systems able to deliver meaningful conventional or nuclear payloads to shape the military balance in a theater of military operations. They can offset U.S. conventional superiority, and pose genuine challenges in conventional warfare. What does Avangard do for Russia that existing silo-based, road-mobile, air-launched, and submarine launched missiles cannot?

The Avangard system is best seen as one element in an expensive Russian strategy to develop technological hedges for a security environment perhaps 20-30 years from now where the United States might deploy a cost effective missile defense system, making a percentage of Russia’s nuclear deterrent vulnerable to interception. To be clear, there is no missile defense system now, or on the horizon, able to intercept Russia’s strategic nuclear arsenal. Modern ICBMs can come with multiple reentry vehicles and numerous penetration aids or false targets, creating a complex ‘threat cloud’ that would make interception an improbable business. Nonetheless, ever since the Bush administration chose in 2002 to exit the 1972 ABM Treaty, Russian leadership has been concerned that the United States could eventually devalue the deterrence provided by Russia’s strategic nuclear forces.

Russia’s General Staff worries that a vast arsenal of long range conventional cruise missiles, paired with a semi-viable missile defense, would pose major challenges for their calculations to ensure the ability of Russian nuclear forces to deliver ‘unacceptable’ or ‘tailored’ damage in the coming decades. The 1972 ABM Treaty was not just a cornerstone of Cold War arms control, but fundamental to Russian military thinking on strategic stability, based on mutual vulnerability at the strategic level. Ever since June 1941, Soviet, and subsequently Russian, military thought has been wracked by the possibility of a disarming first strike, and the need to position Russian forces along a strategy of ‘counter-surprise.’

However, unlike other expensive strategic projects, such as the Poseidon nuclear powered torpedo, Avangard does not contribute to a survivable second strike. Thus there are a few ways to interpret the actual purpose of this weapon. The first is as a retaliatory-meeting strike system to attack high-value targets, i.e. civilian targets with political or economic significance, which will provide some insurance for a counter value strike. The second is that it is a first strike weapon against hard to penetrate targets. Since Avangard is silo based, designed for heavier liquid fueled ICBMs, in the event of strategic attack the boosting missile would not be survivable. It must be fired either first, or in a “launch under attack” scenario, when Russia has confirmed a U.S. launch, but the missiles have not yet impacted.

Avangard may be designed to give Russia’s RVSN the ability to penetrate hard targets, getting around missile defenses, and leveraging greater accuracy to take out well-hardened facilities. That said, from a nuclear warfighting standpoint, this makes Avangard a somewhat specialized, but expensive strategic nuclear weapon. Given how few of these systems Russia is likely to be able to afford, the weapon may offer some targeting advantages, but at a high price relative to the benefits. Another possibility is that this is not a system to get around future missile defenses, but a first strike system to be used specifically against missile defenses, clearing the way for the rest of Russia’s nuclear deterrent. Even if more accurate and survivable in flight, Avangard is a questionable investment when compared to the numerous road-mobile ICBM systems Russia fields today, including Topol-M and Rs-24 Yars (but then the logic for Russia’s SSBN program is also somewhat circumspect).

Perhaps in the future, Avangard will be deployed on a road-mobile launcher, but as conceived, this system adds little to Russia’s existing large strategic nuclear arsenal. An expensive insurance policy that in no way alters the strategic nuclear balance either today or tomorrow, which is why the reaction in Washington has been so muted. If anything, the United States should thank Russia for investing money in such super weapons, instead of buying large quantities of conventional precision guided munitions.

Moscow has sought to leverage Avangard and similar novel systems to sell the notion of a qualitative arms race to Washington, D.C., hoping to establish a bilateral agenda for summits. Yet while the world is genuinely witnessing a renewed period of nuclear modernization, with qualitatively new or novel weapon systems in development, there is no arms race in progress. The major nuclear powers of today are pursuing distinctly divergent strategies, concepts, and requirements behind their nuclear weapons programs, rather than racing which each other for superiority. This is why Avangard, if completed and deployed, is unlikely to alter strategic military balance or elicit any meaningful response from Washington, D.C.

I think that from military point of view your analysis is good as always, but IMO Avangard and Poseidon have a significant political reasoning behind them. From some statements made by Putin it seems that the Russian leadership is hedging against an irrational US leadership coming to the (false) conclusion that the US can send some ICBMs towards Russia and deflect a counter-strike with its ABM. I know that to a rational observer this seems crazy, but it seems that Russian leadership is considering US political elite to be on a downward slope rationality-wise. It has probably begun long time ago, after 2001, when the people in Bush Jr.’s presidency associated with Project for the New American Century started to push PNAC’s agenda as the official US agenda.

So, the Russian leadership (which is the same since 2000 so has a big advantage in implementation of long-term projects) wants not only weapons that would deter a rational person (like you or me) but also any exceptionalism-infested neocon. Their unbeatability has to be obvious and undisputable.

LikeLike

Its not an issue of rationality. The possibility of select counter force has been a factor ever since 1974 change in U.S. planning to limited nuclear options (LNOs) under Schlesinger. There was always a difference in that the USSR did not believe limited strategic exchange could be contained, and escalation limited. The strategy was not especially credible because the U.S. held no force advantages back then, so it would be self-deterred from such options. An argument could be made that viable missile defense creates an opening for the U.S. to believe it has limited nuclear options, creating a window for negotiations. However, the problem with this thinking is that a limited U.S. nuclear strike with counterforce in mind could just target these few ‘Avangard’ carriers in fixed silos.

The problem is also entirely one of boxed logic. There is no reason to believe that a missile defense system designed for X missiles would simply not invite a retaliation by Y missiles. Unfortunately parts of the strategy community believe in what I call the ‘nuclear trebuchet dilemma’ – that is, if someone builds a nuclear trebuchet, it can only be deterred by a nuclear trebuchet, even though any number of other systems, yields, and so on would do. Hence, the existence of something as ridiculous as a nuclear trebuchet would result in an asymmetry, and a ‘trebuchet gap’ on which many articles will be written.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you think that Avangard will be only on silo-based missiles? They’re using the UR-100N for now because it was available, and of course it makes sense to use Avangard for the new RS-28, classic RVs are sooo the 1980’s 🙂 But as I understood it, the original plan was to use also the mobile RS-26, and I think they’ll get back to it once budget permits, for now the RS-28 has priority. They’re safe against the current capabilities of US ABM so they can do it in the next armament program after 2027.

As for Avangard and the ‘no mineshaft gap’ policy, it seems to me that Russia does not continue the Soviet doctrine. They needed to counter a possible future working ABM defense. They had three options – a viable comprehensive ABM defense of their own (ridiculously expensive if it is even possible), ridiculous numbers of classic RVs (also extremely expensive, and they would need to forget about nuclear arms limitation treaties), or something that could so clearly beat any ABM defense that nobody in the US would consider its ABM defense able to defend anything. This was the most economic option, they went with it, and now they have results…

Do you plan to do an article on future Russian carriers? I’ve read that they’re developing a VTOL aircraft (first said by Borisov back in 2017) and that they won’t go with Shtorm (of course) or even the Lavina/Priboy concept, instead they want something that can land ground forces while at the same time carrying also helis and VTOL aircraft. Economic option once again…

LikeLiked by 1 person

RS-26 was a piece of misinformation from years ago. It does not have the throw weight, and I do not think it was ever meant for a HGV. Next generation ABM may intercept HGVs, so I’m not sure how sound of an investment it really is. Might have been much cheaper to go with alternative missile defense defeat systems.

I don’t think there will be future Russian carriers, or VTOL aircraft. Unless Indians are silly enough to pay for such programs. There will be a LPD ship of the Dutch style such as Rotterdam, in the 12,000-14,000 displacement range. Russian MoD officials love making announcements to drive the news cycle, but most of this is nonsense. Don’t expect to see anything laid down until the end of this state armament program.

If you dig through this blog you can find several entries covering Russian naval development programs and amphibs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

On Soviet Doctrine. It depends what you’re referring to. Russia maintains Soviet plans for theater nuclear strike, while at the same time not accepting the possibility of limited nuclear war between homelands, i.e. limited strategic nuclear options.

For implications, I offer one opinion from Robert Jervis:

“Neither side can employ limited nuclear options unless it is quite confident that the other accepts the rules of the game. For if the other believes that nuclear war cannot be controlled, it will either refrain from responding-which would be fine-or launch all-out retaliation.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

this weapons system should be as good as the armata tank, putin was yelling about.

LikeLike